Shinzen Young

We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time.

–from T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding”

I. SOME USEFUL DISTINCTIONS

What pops into your head when you hear the word “mindfulness”? After nearly half a century of practice, teaching, and research in this field, here’s what comes up for me.

When I hear the word mindfulness without further qualification, I don’t think of one thing. I think of eight things. More precisely, I see a sort of abstract octahedron—one body with eight facets. The eight facets are:

1. Mindfulness – The Word

2. Mindfulness – The Awareness

3. Mindfulness – The Practices

4. Mindfulness – The Path

5. Mindfulness – The Translation

6. Mindfulness – The Fad

7. Mindfulness – The Shadow

8. Mindfulness – The Possible Revolution

It has been my experience that carefully considering each of these aspects helps dispel a lot of confusion and contention. First I’d like to touch on each briefly, then discuss some of them in more detail centering around the issue of how to define mindful awareness.

Mindfulness – The Word

It’s important to remember that mindfulness is merely a word in the English language. As such, its meaning has evolved through time and it may denote different things in different circumstances.

When speaking of non-Western cultures, it is common to distinguish the pre-contact situation from the post- contact situation. Contact, in this case, refers to interaction with modern Europeans.

Here’s an example. Before contact with Western ideas, the Japanese word kami referred to the local Shinto god(s). Contact with Abrahamic religions caused a semantic broadening. Kami can still refer to a particular Shinto god, but it can also stand for the Western monotheistic notion of God/Deus/Elohim.

But contact is a two-way process. Prior to contact with Asian culture, the English word mindfulness meant something general like heedful or aware of context. After contact, it could still be used in that general way but more and more it has come to designate a very specific type of awareness. It is mindfulness in that specialized sense that I seek to clarify in this article.

We can distinguish several stages in the development of “post-contact mindfulness.”

In the 19th century, mindfulness was used to translate the Pali word sati. Pali is the canonical language of Theravada. Theravada is a form of Buddhism found in Southeast Asia. Among surviving forms of Buddhism, Theravada is thought to be the closest to the original formulations of the Buddha. Satipaṭṭhāna (“Establishing Mindfulness”) is a representative practice of Theravada.

In the 60s and 70s, Westerners began going to Southeast Asia to learn mindfulness practices. They brought those practices back to the West and began to teach them within the doctrinal framework of Buddhism.

In the 80s and 90s, it was discovered that those practices could be extracted from the cosmology of Buddhism and the cultural matrix of Southeast Asia. Mindful awareness practices (MAPs) started to be used within a secular context as systematic ways to develop useful attentional skills. MAPs became ever more prevalent in clinical settings for pain management, addiction recovery, stress reduction, and as an adjunct to psychotherapy. Eventually it came to be understood that mindful awareness is a cultivatable skill with broad applications through all aspects of society, including education, sports, business, and even the training of soldiers.

As the word mindfulness in its “post-contact” sense gained popularity, people naturally began to ask “How do we define mindful awareness?” I think it’s safe to say that we do not have a really satisfactory definition of mindful awareness. Yet we sense that it’s a distinct entity of some sort and that it may have the potential to contribute significantly to human flourishing. So we find ourselves at that deliciously excruciating point in the development of a new science where we know we’re on to something but we can’t quite tie up all the loose ends. For that reason, it’s important not to fool ourselves into thinking we understand more than we do.

The ultimately satisfactory definition of mindful awareness would be a biophysical one—couched in the language of SI units and mathematical equations modeling the neural correlates of mindful states and traits. We are decades, if not centuries, away from that kind of rigor.

That kind of rigor will result from research. But in order to begin research on something, we have to first define it. So it would seem that we are in a sort of catch-22 situation here.

One way out is to begin with a tentative definition and then refine it over time. In Section III, I offer a candidate for that and justify it from numerous points of view.

Side note: Although there exist traditional Sino-Japanese words corresponding to sati, satipaṭṭhāna, and such, the modern Japanese word for mindfulness (maindofurunesu) is derived from English. This could perhaps be taken as an example of post-post-contact linguistic change—an Asian language being influenced by a Western word that has been influenced by a (different) Asian language!

Mindfulness – The Awareness

The word mindfulness can, for one thing, denote a specific form of awareness or attention. When we wish to speak carefully, we should refer to this as mindful awareness.

It is customary to distinguish state mindful awareness (how mindful a person happens to be at a given time) from trait or baseline mindful awareness (how mindful a person is in general).

Mindful awareness is often defined in terms of focusing on present experience. In Section III, I’ll offer a detailed analysis of that notion and propose a somewhat more fine-grained formulation. In Section IV, I’ll discuss whether the proposed refinement represents an improvement.

Mindfulness – The Practices

Mindfulness can also refer to the systematic exercises that elevate a person’s base level of mindful awareness. Once again, in careful usage we should refer to these as mindfulness practices or, more fully, mindful awareness practices (MAPs).

Two of the most common MAPs are Noting and Body Scanning. Both of these were developed in Burma and appear to date from the early 20th century. Body Scanning is associated with U Ba Khin who was a highly respected official in the Burmese government. Noting is associated with Mahasi Sayadaw who was a famous scholar monk.

Based on the broad way I will be defining mindful awareness, the following could also be considers MAPs:

• Loving kindness (and more broadly the Brahmavihāras practices)

• Open presence (Choiceless Awareness, Do Nothing, etc)

Mindfulness – The Path

A person’s base level of physical strength can be dramatically elevated through a well-organized regimen of physical exercise. Analogously, a person’s base level of mindful awareness can be dramatically elevated through a well-organized regimen of mindful awareness practices. But so what? Why, in specific, is mindful awareness a good arrow to have in one’s quiver of life skills?

Well, it turns out that mindful awareness is not just an arrow. It is more or less the arrow—a tool of immense power and generality that can be applied to improving just about every aspect of human happiness.

I use the phrase “Mindfulness – The Path” for the process of applying mindful awareness to achieve specific aspects of human happiness. I like to classify those aspects under five broad headings. Mindfulness can be used directly to:

• Reduce physical or emotional suffering.

• Elevate physical or emotional fulfillment.

• Achieve deep self knowledge.

• Make positive changes in objective behavior.

• Develop a spirit of love and service towards others.

In addition to its direct effect on a person’s happiness, mindful awareness can also have significant indirect effects. That’s because mindful awareness potentiates the efficacy of other growth and self help processes. From body work, through the spectrum of psychotherapies, up through a person’s introspection and prayer life—every growth modality becomes more powerful when implemented on a highly mindful platform.

Mindfulness – The Path has two sides:

• The theoretical side

• The practical side

The theoretical side seeks explanatory mechanisms.

• By merely directing attention in a certain way, a person can dissolve intense physical pain into a kind of flowing energy—and do so consistently. How do we explain this? What specific mechanisms are involved?

• By merely directing attention in a certain way, a person can come to an empowering “I-Thou” relationship with the world. How do we explain this? What specific mechanisms are involved?

• By merely directing attention in a certain way, a person can break the spell of a long-standing destructive habit. How do we explain this? What specific mechanisms are involved?

The practical side involves organizing and packaging MAPs into dedicated programs that address the interests and needs of specific populations.

In Section V, I’ll describe in detail one specific theoretic model: how mindfulness reduces suffering.

My colleague Soryu Forall’s Modern Mindfulness for Schools program (www.cml.me) is an example of a practical application. It organizes a subset of my Unified Mindfulness System (formerly Basic Mindfulness System) into an Internet product for classroom use.

I sometimes find it useful to think in terms of “systems of mindfulness”. A system of mindfulness (SOM) is a triple:

• A theory of mindful awareness and related topics.

• A set of specific techniques (i.e., practices).

• A set of guidelines for applying mindful awareness toward specific goals (i.e., a path).

One convenient feature of mindfulness is that a small set of techniques can have a wide range of applications. An SOM can be very narrow in its target or quite broad. At the narrow end would be tightly dedicated programs such as:

• Mindfulness for pelvic pain syndrome

Or

• Court-ordered mindfulness-based anger management.

At the broad end would be what I refer to as a comprehensive system of mindfulness (CSOM). A CSOM has two characteristics:

• Its application guidelines cover the full spectrum of human issues.

• Its users are encouraged to apply mindfulness as broadly as possible to all aspects of their life.

Specifically, a CSOM encourages the user to apply mindful awareness to achieve the “ABCs of Human Goodness.”

• Affect – Cultivate habitually positive emotional states.

• Behavior – Make needed changes in objective behavior.

• Cognition – Reinforce rational, adaptive thought patterns. Unified Mindfulness mentioned above is an example of a CSOM.

In Southeast Asia, ethics and good character (sīla) are often looked upon as a necessary precursor to mindfulness practice. On the other hand, training in positive affect (loving kindness, etc.) is often looked upon as a desirable add on to mindfulness practice.

But these elements can be sliced and diced in a different way.

If we wish to make skill acquisition the point of entrance, then character and behavior become a specific application of mindfulness skills. This is useful in the multicultural setting where people may have different ideas regarding behavioral norms.

Furthermore, practices such as loving kindness can be done in a way so that they strengthen a person’s basic attentional skills: concentration, clarity, and equanimity. Therefore, they fulfill my rather broad definition of a mindful awareness practice. But they also foster the ABCs of human goodness. In that regard, they can be looked upon as applications of mindful awareness, i.e., in intrinsic part of the path of mindfulness.

What is revolutionary about mindfulness is that it makes acquisition and application of attentional skills the centerpiece for (potentially radical) psycho-spiritual growth. It can therefore sidestep some of the contentious issues surrounding historical movements where the centerpiece is often acceptance of a belief structure combined with assent to a detailed list of rules.

Mindfulness – The Translation

There is a lot of public disagreement about what mindfulness “should” mean. Part of this stems from the fact that the English word mindfulness can be used to translate various Asian terms. Someone who wants to be faithful to a specific Asian usage may insist on defining mindfulness in a rather narrow way. On the other hand, people who are excited by “Mindfulness – The Possible Revolution” tend to define it in a broader way, and may not require that it stand for a specific Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese, or Tibetan word.

Mindfulness was originally used to translate the Pali word sati but it can more loosely refer to a number of other closely related terms of Indian origin. Mindfulness may connote:

| Sanskrit | Pali |

| smṛti | sati |

| smṛtyupasthāna | satipaṭṭhāna |

| vipaśyanā | vipassanā |

| vipaśyanābhāvanā | vipassanābhāvanā |

There are specific Tibetan and Chinese words that correspond to these Indic terms. The Pali words are currently used in Southeast Asia. The Sanskrit words were used in India during the middle and late Buddhist period. The Tibetan versions are used in Tibet. The Chinese versions are used in East Asia (China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam).

Things can get contentious and confusing if we try to make the English word “mindfulness” correspond to exactly one Asian term. Here’s why. Although the words listed above are closely related, they are not quite synonyms. Moreover, Southeast Asian, East Asian, and Tibetan traditions do not necessarily agree among themselves as to how to define those terms. Indeed, even within a given cultural area, there can be disagreement among different scholars and lineages as to what a given term specifically designates.

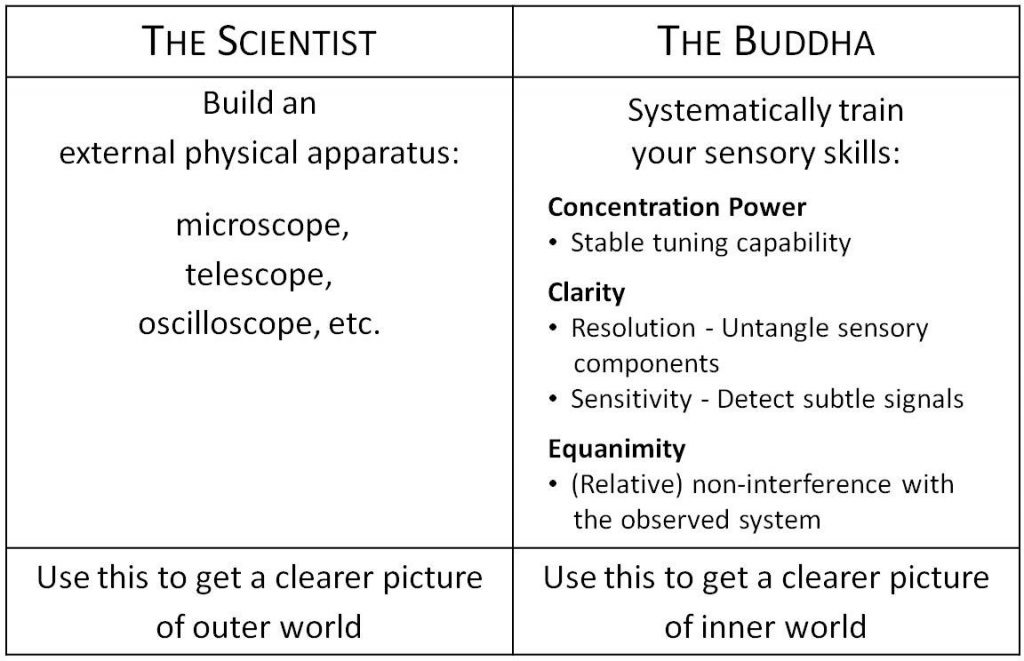

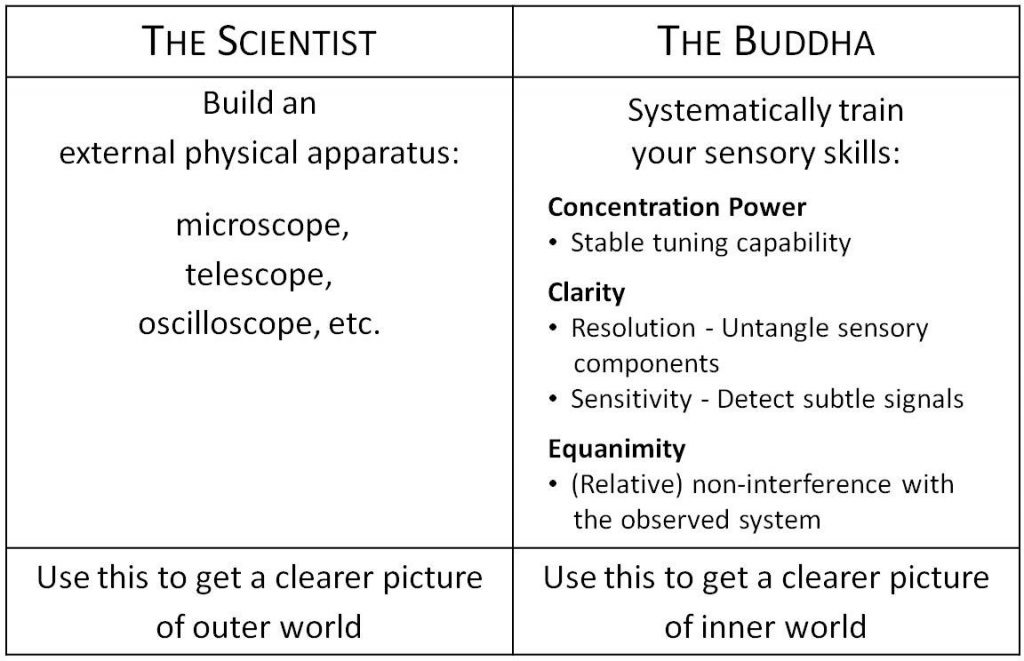

I and some other teachers (most notably Jon Kabat-Zinn) would prefer to not require that mindfulness directly correspond to any specific Asian term. For me, mindfulness designates any growth process based on acquiring and applying concentration, clarity, and equanimity skills and capable of providing industrial strength effects.

Epilogue

How do you say “mindfulness” in Tibetan?

Unified Mindfulness is the name of a SOM I created. It’s the first (and to my knowledge only) comprehensive system of mindfulness specifically designed to help scientists answer basic questions about the nature of consciousness. It does that by classifying sensory categories and focusing strategies in a way that is convenient for analyzing neuroimaging data. It is currently being used in neuroscience labs at BWH and MGH (both parts of Harvard Medical School).

It is well known that the Dalai Lama of Tibet is interested in and supportive of scientific research on contemplative practices, Buddhist and otherwise. Soon after we got the results of our first research at Harvard Medical School, our Principal Investigator Dave Vago was invited to meet with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Dave wanted to describe our research and asked me how to say “mindfulness” in Tibetan. I immediately realized that we had a problem. If we take mindfulness to be the translation of the Pali word sati (Sanskrit smṛiti), then the answer is simple. The Tibetan word for mindfulness is dran.pa. (pronounced something like “chemba”). But for Dave and me, “mindfulness” is a much broader concept. For us and some other people in the field, mindfulness is essentially a secularized and streamlined reworking of some of the Buddha’s main discoveries—discoveries that can be made evidence based and organized around the notion of acquiring and applying attentional skills.

There is no term in Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese, or Tibetan corresponding to mindfulness in that sense.

So how could we convey our understanding of mindfulness in a Tibetan word that would be meaningful to the highest authority in the world on Tibetan Buddhism? A fascinating challenge.

I got together with a team of friends who have a good knowledge of Tibetan and understood the nature of the problem. We’re all Americans but of diverse ethnic provenance. Eventually we came up with a remarkably good candidate.

It turns out that the Tibetan language has a way to solve problems like this. The word lam (literally “path”) implies a comprehensive system. If you preface it with something, say X, it forms a word meaning

“a comprehensive system based on X”.

So we came up with dran.lam (short for dran.pa.lam).

Afterwards, I thought to myself, what a wild, wonderful age we were living in—

an Irish-Lebanese-Puerto-Rican-Jewish team concocting a Tibetan neologism so as to convey to the Dalai Lama a way of radically revisioning Buddhism!

Mindfulness – The Fad

Mindfulness is currently a sizzling hot topic in many areas of mainstream Western culture. The downside of this is that some programs being marketed under the rubric of mindfulness have at most a tenuous connection to the practices and paradigms that are the subject of this article. Specifically, they completely fail to capture its potential for radical transformation and unconditional happiness. But it’s precisely this potential for radical transformation that old-timers like me find most exciting. I think of mindfulness as the big guns—something that helps when nothing else can.

The situation is reminiscent of what happened to the word biofeedback. Biofeedback is a well-defined physiological process which erupted into celebrity in the 1970s and continues to be studied to this day. But as soon as the term became well known, numerous products and processes calling themselves biofeedback flooded the self-help market. Many of these had not the slightest connection with what physiologists refer to as biofeedback.

Mindfulness – The Shadow

So far my glowing depiction has made mindfulness sound a bit like the Shmoo. The Shmoo is a fictitious creature that appeared in the cartoon series Li’l Abner. The Shmoo creature is endowed ludicrously with many desirable features and not a single undesirable one. Is mindfulness like that? Not quite.

Much of what appears in the literature of mindfulness describes what I would call Mindfulness Lite. In this article, I will be emphasizing the importance of also understanding Mindfulness Classic—the industrial strength end of the spectrum. Two groups gravitate towards Mindfulness Classic.

• Group I. People seeking deep transformation/transpersonal experience/spiritual praxis.

• Group II. People facing challenges so huge that nothing short of the big guns will help.

Many people—probably most—will find themselves in Group II at least once or twice in a lifetime. So from that perspective, it’s important for anyone in the mindfulness field to understand Mindfulness Classic, specifically:

• To appreciate its potential payoffs.

• To know about its possible problems.

How dramatically a person changes as the result of mindfulness practice depends on several variables:

• The amount of time they devote to practicing techniques.

• The type of techniques they use.

• Their personal goals.

• What their guide tends to emphasize.

Devoting more time to practice tends to speed up change; reducing time spent in practice tends to slow down change. As a general principle, deconstructive techniques move change in the direction of experiencing ego transcendence. (The “Return to the Source” process described at the end of Section V is an example of a deconstructive technique.) Reconstructive techniques move change in the direction of ego strength. (Loving kindness is an example of a reconstructive technique.) Tranquilizing techniques move change in the direction of emotional regulation. (Certain kinds of breath practice are examples of tranquilizing techniques.)

As with any growth process (psychotherapy, for example), there’s always the possibility that mindfulness will bring up too much too soon. So, people considering intensive programs should be informed beforehand of the range of phenomena they may encounter.

So what to do if too much comes up too soon? The remedy is relatively straightforward:

• Change the techniques

and/or

• Reduce the amount of time devoted to practice.

The most dramatic transformation associated with mindfulness is transpersonal experience. Transpersonal experience brings about a shift in one’s perception of self. When that change begins to occur, there may be a period of adjustment to the new, less solidified, less separated mode of being. Most people have no difficulty making that adjustment because the new state is so deeply fulfilling, insightful, and empowering.

However, occasionally people encounter serious difficulty accommodating to an attenuated and unfixed perception of self. This difficult stage is sometimes referred to as the Dark Night. Four points need to be made immediately.

1. This phenomenon is completely different from the “too much too soon” situation mentioned above. It’s a distinct critter and typically requires specialized and intensive support.

2. There is a well-defined way to provide that support. It works reliably but may require a bit of time (perhaps several years).

3. Once a person has gotten through the Dark Night, they come to an abiding happiness beyond anything they could have imagined possible.

4. The Dark Night phenomenon is relatively rare—even among people who engage in the industrial strength level of mindful practice.

So the chances that involvement with MAPs would trigger this issue is rather small. But rather small ≠ 0, and as more and more people take on mindfulness, this phenomenon is bound to surface.

For that reason, it’s important for people in the mindfulness field to:

• Be able to recognize the Dark Night.

• Know how to guide people through it or, at the very least, know how to find someone who knows how to guide people through it.

So how do you guide a person through it?

This would not be an appropriate place to go into the details but I can at least give you the gist of how it’s done. The main take away points are:

• it may require a massive and sustained support effort, and

• it will be well worth that effort.

The Dark Night is a kind of awkward inbetween zone. A classic Johnny Mercer song talks about “Mr. Inbetween.” It unintentionally provides a mnemonic for how to get through the Dark Night quickly.

Jonah in the whale, Noah in the ark,

What did they do, just when everything looked so dark?

You gotta…

Accentuate the positive

Eliminate the negative

And latch on to the affirmative

Don’t mess with Mister Inbetween.

Three focus strategies transform the situation from problematic to blissful.

1. Accentuate the good parts of the Dark Night even though they may seem very subtle relative to the bad parts. You may be able to glean some sense of tranquility within the Nothingness. There may be some sense of inside and outside merging (leading to an I-Thou relationship). There may be soothing, vibratory energy massaging you. There may be a springy, expanding-contracting energy animating you.

2. Eliminate the negative parts of the Dark Night by deconstructing them through careful observation. Remember “Divide and Conquer”—if you can divide a negative reaction into its parts (mental image, mental talk, and emotional body sensation), you can conquer overwhelm.

3. Affirm positive emotions, behaviors, and cognitions in a sustained systematic way. By that I mean gradually, patiently reconstruct a new habitual self based on loving kindness and related practices.

In most cases, all three of these must be practiced and maintained for however long it takes to get through the Dark Night. In the most extreme cases, it may require ongoing and intensive support from teachers and other practitioners to remind the student to keep applying these focusing strategies.

The traditional Buddhist term for this phenomenon is “falling into the Pit of the Void” but modern Western Buddhists often refer to it as the Dark Night. Ironically, that phrase is actually of Christian origin. It was coined by a 16th century Spanish priest St. John of the Cross. His writings contain a vivid description of the challenges involved in this phenomenon and the rewards that await on the other side.

The Dark Night is in some ways the “evil twin” of enlightenment. A person experiences oneness/emptiness/no self but it’s a bad trip (at least for a while).

A related phenomenon can occur suddenly and spontaneously to people who aren’t engaged in any specific practice. The clinical term for this is Depersonalization/Derealization (DP/DR) Disorder. The name pretty much sums up the situation. Could an intervention, such as described above, be helpful for victims of DP/DR? I’m not personally aware of any studies regarding this, however I think it’s an interesting clinical question.

Mindfulness – The Possible Revolution

As mentioned previously, mindful awareness is a skill set. In that regard, it’s no more controversial than learning to shoot hoops or to play the piano. But it’s an attentional skill set and how we pay attention can influence how we perceive and behave. One of the convenient features of mindfulness is its “scalability.” Mindfulness Lite can calm a 6th grader. Mindfulness Mid-Strength can take the edge off of stress and improve your golf game. On the other hand, Industrial Strength doses of mindfulness will allow you to stride through life like a Colossus—in touch with a Happiness that cannot be shaken by circumstances.

Mindfulness is currently in the process of aligning itself with the single most powerful and universally influential institution on this planet—science.

Science is being evoked both to confirm the clinical effects of mindfulness and to develop a theory that explains those effects. It is by no means certain that this line of research will be successful. But IF it is successful, consequences could be historic in magnitude. We would then have:

A process with the potential to radically

change a person for the better

which is based on merely acquiring and applying

a well-defined set of skills

and

which is an accepted part of standard science.

By way of contrast, previous approaches for rapid and radical personal change have been based on the (highly contentious) processes of acquiring a well-defined set of beliefs and have sometimes been at odds with the findings of science.

Conveniently, there is nothing intrinsic in mindfulness that directly conflicts with such faith-based approaches. Attentional skills can be thought of as lying in a dimension that is independent from personal beliefs. Mindfulness has the potential to become a sort of universal hardware platform upon which each person is invited to run whatever philosophical software they wish.

If science is able to come up with a quantified model for what happens at the industrial strength end of mindfulness training, then innovative technologies may make those effects accessible to a significant proportion of humanity, as opposed to the current relatively small group of dedicated adepts. This would in effect democratize enlightenment. I think of this prospect as: Mindfulness – The Possible Revolution.

Summing It Up

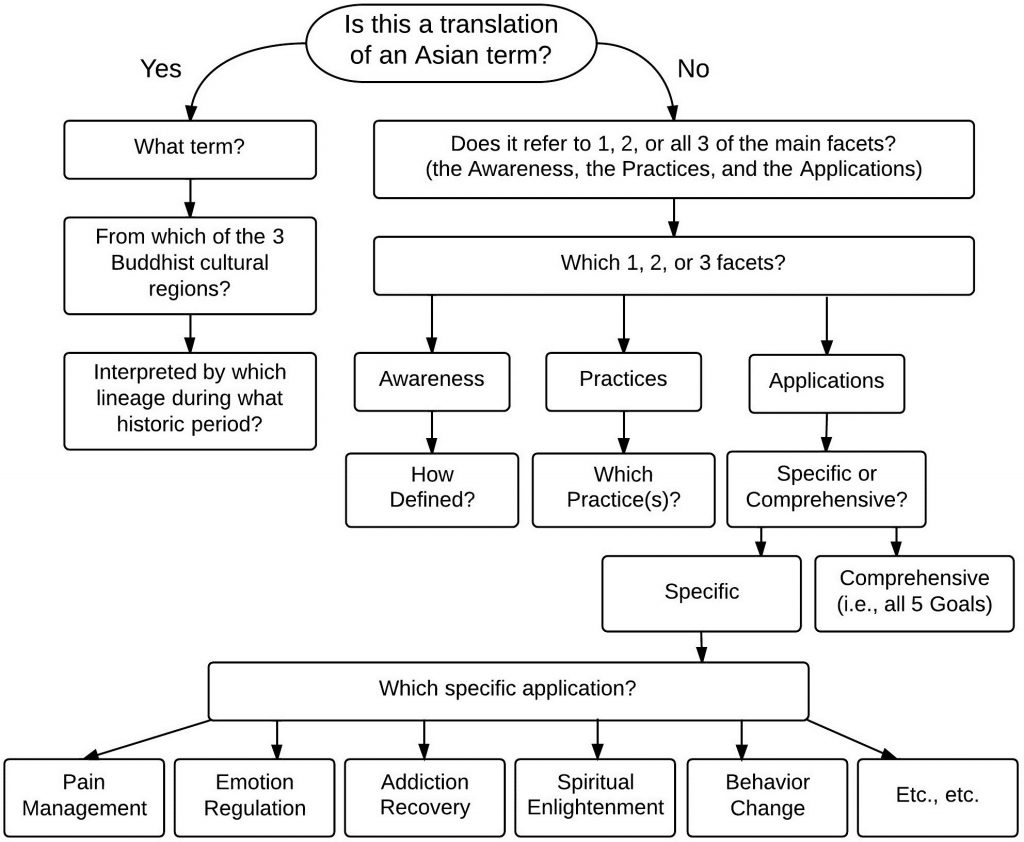

The word mindfulness without further qualification can refer to any one or a combination of three things: a form of awareness, the practices that elevate that form of awareness, and the application of that awareness for specific perceptual and behavioral goals. When we wish to speak with precision, we can use phrases such as mindful awareness, mindful awareness practices, and mindfulness applications (i.e., the path). But often it’s simpler to just say mindfulness and let the context indicate the intended meaning(s). We will be doing that frequently in this article.

To sum things up, here’s a flow chart of what goes on in my mind subliminally when I encounter the word mindfulness without further qualification.

II. NOTING: A REPRESENTATIVE PRACTICE

Introduction

Mindful awareness can be developed through a variety of practices. Among those practices, “Noting” and “Body Scanning” are particularly popular. I tend to take the somewhat broad view that any systematic practice that significantly elevates a person’s base level of concentration, clarity, and equanimity can be counted as a mindful awareness practice. In this way of thinking, even practices such as choiceless awareness, loving kindness, and self inquiry could, in theory, be counted as MAPs if they provide that result.

This would not be the place to attempt an overview of all MAPs. Rather, I’d like to give you a summary of just one: Noting.

Here are the instructions for how to note as defined in the Unified Mindfulness System. It is similar to, but not identical with, Noting as done in the Mahasi tradition.

A period of Noting practice consists of a sequence of acts of Noting. An act of Noting usually consists of two parts:

1. An initial noticing.

2. An intent focusing on what you noticed. This intent focusing may last from a fraction of a second to several seconds. During this intent focus phase, you intentionally soak into and open up to the thing you noted. This is traditionally referred to as “penetrating” or “knowing” the focus object.

Thus, Noting consists of a sequence of noticing and knowing. We will refer to what gets noted as a focus object. Associated with each focus object is a word or phrase—its label. As you note something, you have the option to think or say its label. When you speak the labels out loud, intentionally use a low, gentle, matter-of-fact, almost impersonal tone of voice. When you think the labels, create the same tone in your mental voice. The tone of voice helps put you in a deep state.

The relationship between Noting and labeling and mindful awareness is as follows:

• Labeling can facilitate Noting.

• Noting can facilitate mindful awareness.

• Mindful awareness is a key skill for achieving True Happiness.

Noting need not be accompanied by labeling, and labeling may be mental or spoken. This gives us three possibilities:

1. Just Noting without intentionally labeling.

2. Mental labels accompanying the Noting.

3. Spoken labels accompanying the Noting.

Within the spoken labels there are three sub-types:

1. Sub-vocal labels (mouthed, whispered, or sotto voce labeling that would be inaudible to people near you.)

2. Ordinary spoken labels.

3. Strongly spoken labels.

(Obviously the latter two can only be done in appropriate environments.)

This gives you a spectrum of five possibilities analogous to gear positions in a car. We will refer to these five possibilities as “labeling modes.”

You can freely shift back and forth between labeling modes. You may shift frequently or seldom as circumstances dictate. By circumstances, I mean what is going on inside you (how focused or scattered you are) and what is going on around you (whether there are people you might disturb, etc.). As a general principle, as soon as you get spaced out or caught up, immediately shift to a stronger mode of labeling. Once you get well focused, you can drop to a weaker mode of labeling if you so desire.

| ↑ | Strongly spoken labels |

| Stronger Labeling Mode | Normal spoken labels |

| Sub-vocal labels | |

| Weaker Labeling Mode | Mental labels |

| ↓ | No labels |

Noting the Noting

Making a mental label is obviously an instance of mental talk. Should you note it as such? The answer is no.

Dividing the Attention

As a general principle, put no more than 5% of your attention on the labeling process itself. The other 95% goes into the “knowing.”

An exception to this is the case of strongly spoken labels, which are used when you really “hit the wall” and you need a period of strong feedback to fight with wandering mind and unconsciousness. When using strongly spoken labels, 25% or even more of your attention should go into really listening to the labels. That way as soon as the label stream ceases, you have instant feedback letting you know that you are getting spaced out and caught up.

Some Frequently Asked Questions

1. Question: Noting makes me think a lot. I think about if I’m doing it right. I think about what to look for next. I think about thinking about thinking. What should I do?

Answer: Just be patient. Those are common initial reactions. They tend to go away with time as the Noting categories become more second nature for you and your mind gets tired of playing games with itself.

Another thing you can try is to make your Noting voice more impersonal and matter-of-fact. That may help reduce the “tripping out on yourself” aspect you’re reporting.

2. Question: It seems that a lot of my labels are just guesses.

Answer: That’s okay. You have to start somewhere. Confidence comes with experience.

3. Question: It seems that my labels often come late, after the fact, especially when I’m trying to track mental talk.

Answer: That’s to be expected at the beginning. You are still much more alert than you would be otherwise. With practice, Noting becomes concurrent with the arising of each experience.

4. Question: The Noting seems to interfere with or change the thing I’m focusing on so I can’t detect what’s really there.

Answer: Sure you can. What’s really there is whatever was there plus any change produced from the act of paying attention to it. In this practice our task is (1) to be clear about where we’re focusing and (2) to soak in and savor it. Any sensory experience is a valid candidate for focusing on, even if that experience has been caused by or modified by the act of focusing itself.

5. Question: Noting seems to reinforce a strong sense of an “I” doing the Noting. A: That’s natural at the beginning. At some point the Noting goes on autopilot.

Here’s a metaphor. You can do the complex task of driving a car without needing much of a “driving self.” In the same way, eventually you will be able to quickly and accurately label complex phenomena without needing a “meditating self.” When that happens, the sense of distance between noter and noted collapses.

6. Question: I just keep labeling the same thing over and over again. What’s the point?

A: Remember that Noting is not just noticing. Each time you note something you should intentionally soak into it and open up to it. In other words, you should intentionally infuse clarity and equanimity into what you note, each time you note. When you note that way you are helping deep mind learn a new way to process experience. You are not wasting your time even if you just note the same banal thing over and over.

I know that this can be challenging, because initially you may not get any immediate positive feedback to indicate that something is changing deep down. At some point, though, you begin to sense your awareness

penetrating into the thing noted, softening and purifying the sensory circuits that lie below. When that happens, you start to get immediate tangible feedback that the Noting is doing something useful, and you don’t begrudge the fact that you’re noting the same thing over and over.

7. Question: Why should I note and label?

Answer: There are many reasons. Here are a few.

• The gentle loving tone that you create in your voice as you label can be very powerful. Your own voice can put you into a deep state of reassurance, safety, and self-acceptance. We’ll refer to such a state as equanimity.

• Noting allows you to focus on just what’s present in the moment. This reduces overwhelm, which in turn reduces suffering.

• Noting allows you to break experiences down into manageable parts and deal with them one at a time. A 500-pound weight will crush you, but ten 50-pound weights can be carried one at a time.

• Several of the focus objects represent windows of opportunity—pleasant aspects of experience (such as rest and flow) that are often present but usually go unnoticed and, hence, un-enjoyed. Sensory categories used in Unified Mindfulness are set up to call your attention to such windows of opportunity.

8. Question: I cannot seem to separate mental image from mental talk. Any suggestions?

Answer: It depends on what you mean by “separate.”

If by separate you mean preventing image and talk from happening at the same time, or stopping them from interacting back and forth, then you’re right. Neither you nor anyone else can separate them in that sense. However, the good news is that there’s no need to separate them in that sense. Even when mental talk and mental image are intertwined, it is still possible to experience them as qualitatively and spatially distinct sensory events.

Qualitatively speaking, mental image is visual. Mental talk is auditory. Spatially speaking, image tends to be centered more forward. Talk tends to occur further back, in your head.

Just as you can distinguish external sights from external sounds, you can “separate” internal images from internal conversations.

9. Question: Can you summarize some basic guidelines for the labeling process?

Answer:

• If you are noting without labels and are getting spaced out or caught up, start to mentally label.

• If that doesn’t help, modulate your mental voice to be more gentle and matter-of-fact, even if that seems artificial and contrived.

• If that doesn’t help, speak the labels out loud in that gentle and matter-of-fact tone.

• If that doesn’t, use strongly spoken labels.

• If the effort to speak the labels causes uncomfortable reactions (resistance, emotion, and so forth) label those reactions. (Those reactions are proof that you’re doing the procedure correctly. The stronger labeling mode is forcing you to go toe-to-toe with the unconsciousness itself!)

10. Question: I don’t like to label.

Answer: The solution is easy. You don’t have to! Labeling is an option within the apparatus of Noting. But if it’s a choice between effortful labeling on one hand and being grossly spaced out on the other, go for the labels!

III. TOWARDS A DEFINITION OF MINDFUL AWARENESS

Desiderata

Characteristics of a Good Definition

Before discussing how mindful awareness might be defined, it would be useful to consider what characteristics a good definition should possess. For me, four things come to mind. I’d like my definition of mindful awareness to be:

• Intuitive

• Quantitative

• Explanatory

• Historical

Intuitive

By intuitive I mean easily understood by the average person. After all, if mindfulness is a good thing, then we want people from all educational and social backgrounds to embrace its practice. This will be easier if mindful awareness can be described in a way that is relevant to most people’s experience. Stated in somewhat crass terms, we would like our definition of mindful awareness to be such that the average person will readily “buy into” it.

Quantifiable

Quantifiable is short for quantitative in a rigorous way. By that I mean something a hard-nosed scientist would be comfortable with, something “operational”—ideally something measurable in biophysical terms.

Explanatory

I’d like my definition to be convenient for forming hypotheses that explain observed effects. In Section I, I listed five broad headings under which the effects of mindfulness could be classified. Each of those headings contain numerous subheadings. Are the mechanisms that explain this wide spectrum of effects identical or are different mechanisms at work for different effects? In either case, we would like our definition of mindful awareness to help explain, in a plausible and detailed way, how the left hand side of the formula below is connected to the right hand side.

Applying generic attention skills ⇒ specific improvements with respect to a perception or a behavior

Historical

Historical is short for historically heuristic. Something is heuristic if it is capable of providing insight (heureka). A historically heuristic definition of mindful awareness would allow us to understand its relationship to other states of consciousness that have been known throughout history and across cultures. As a corollary, it would

clarify the relationship between mindful awareness practices and other practices, both pre-modern (e.g., yoga, Christian contemplation) and contemporary (e.g., psychotherapy, 12-Step Program, etc.).

A Common Definition

The most commonly encountered definition of mindful awareness is something like:

“Present-centered, non-judgmental attention.”

Let’s begin with that.

Definitions should be as unambiguous as possible. Different people may have different ideas as to what it means to be present-centered or non-judgmental. Perhaps by reviewing a range of examples, we’ll be able to bring more clarity to the issues involved. Hopefully that will allow us to refine and rigorize our formulations.

Present-Centered

Consider the following.

Present 1: Sight, Sound, and Body is Now

You focus on physical sights, physical sounds, and (physical and emotional) body sensations as they arise. If you get caught up in a thought, you let go of that thought and bring your attention back to a physical sight, physical sound, or a body experience.

Clearly, content-wise, sights, sounds, and body events keep you in the present. Any content unrelated to the present will come up as thought—remembering, planning, rehearsing, fantasizing, and so forth.

So this practice would lead you to being present-centered. Indeed some people would define present-centered in terms of a practice like this. In that formulation, present-centered means being anchored in physical senses and body experience with little or no intrusive thought.

Consider yet another possibility.

Present 2: Breath is Now

You focus on your breath. If your attention is pulled to anything else, you return to focusing on the breath. You try to detect each in-breath and each out-breath as a distinct event. If they feel different, you note that difference. You try to detect the very instant when the in-breath begins and the very instant when it ends; likewise for the out-breath.

For many people, example 2 might result in a “tighter” experience of the present than example 1.

Analysis

Let’s make a careful analysis of these examples.

Both involve selective attention. In the first case, you intentionally focus on a certain class of sensory experience and intentionally pull away from anything that’s not in that class. In the second case, you do the same but focus on an even narrower class of sensory experience.

So in both cases, the “centered” in present-centered indicates that you’re intentionally focusing on a specific type of sensory experience—sensory experience that is intrinsically free of memory, planning, or fantasy content. Clearly, both exercises build concentration power. On the other hand, to do either exercise well requires concentration power.

Besides concentration power, are there any other attentional skills involved in these examples?

The first example seems mostly to involve concentration. Attention wanders into thought, bring it back to sight, sound, body! It wanders again, bring it back! It wanders again…. Each rep strengthens your concentration muscle.

There does seem to be a new element in the second example. Here you’re also being asked to make distinctions and discriminate the sensory qualities of the in-breath from the sensory qualities of the out-breath. You’re also asked to detect temporally fleeting events: the very instant the in- or out-breath begins and the very instant the in- or out-breath ends. The reason example 2 is temporally tighter is not because the focus is more narrow than example 1 (that’s merely a spatial feature). The reason example 2 is more in the Now is because:

1. The information processing channel is being saturated with data.

2. Subtle events, in particular subtle temporal events, are being detected. The first factor might be thought of as resolution power or discrimination ability. The second factor might be thought of as a sensitivity or detection ability.

Both could be grouped within a more general category which, for lack of a better term, we will call sensory clarity.

So sensory clarity involves resolution power and sensitivity. By resolution power, I mean the ability to distinguish qualitative, quantitative, and spatial differences. By sensitivity, I mean the ability to detect subtle sensory signals, spot fleeting events, monitor continuous rates of change and so forth.

Evidently, concentration power and sensory clarity are basic attentional skills needed to be present-centered.

The observant reader may have noticed that there’s an inherent limitation in both of the examples presented so far. They both involve selectively focusing on a certain type of sensory experience. Or, more to the point, they both involve focusing away from a certain type of sensory experience—thoughts. Now it is certainly true that, in terms of content, thoughts can be about past, future, or fantasy, but as sensory events (mental images and mental talk), they occur in the present. It would be satisfying if we could be present-centered with regard to all sensory events, including thoughts. To include thoughts as part of “Now”, you need to do two things.

1. Be clearly aware when each thought begins and when it ends.

2. Not be caught in the thought as it is happening.

It’s the “caughtness” in the thought that pulls us out of the present and into past, future, and fantasy content.

The first point involves an attention skill we’re already familiar with—sensory clarity. The second point introduces a new element—“not-caughtness.” Not-caughtness is a kind of hands-off relationship, a balance point that avoids both pushing down and grasping on. Our technical term for this skill will be equanimity (from the Latin for “inner balance”).

So it would seem that we can be present-centered without restriction with regard to sensory content as long as we have…

• Enough clarity to detect arisings and passings and discriminate sensory qualities.

• Enough equanimity to avoid getting caught up in things. Here’s a description of how to do that.

Present 3: Everything is Now

You let your attention go wherever it wants to go. Whenever something arises to prominence, you focus intently on it, trying to experience it in all its sensory richness. You welcome each new experience but try not to grasp on or get caught up. Moreover, you’re alert to detect the very moment when each sensory event arises and the very moment when it passes.

In Present 1 and Present 2, you needed concentration power to focus away from thought. In Present 3, you’re not focusing away from anything. There’s no specified thing that you’re coming back to. So does that mean that concentration power plays no role here?

Well, it turns out that concentration power comes in several “flavors.” One flavor is durative. The durative involves holding attention in a restricted domain for an extended period. The domain may be qualitatively restricted (just one class of sensory experience as in example 1). The domain may also be spatially restricted (just one location as in example 2).

The durative flavor is what most people think of when they hear the word concentration. But there’s also a momentary flavor of concentration. This involves briefly but intently focusing on each sensory event as it comes up. Even though your attention may be broadly floating within a wide range of sensory experience, you briefly “taste” a moment of high concentration with each thing as it arises.

The momentary flavor of concentration power is very important in mindfulness practice—so important that there’s even a technical term for it in Pali. The term is khaṇikasamādhi.

So concentration enters into any definition of present-centeredness. If we define present-centered as selective attention to present content, then we need the durative type of concentration power to hold that content with unbroken attention. If we define present-centered so it’s applicable to any type of sensory content, then momentary concentration is relevant.

We also saw that if we wish to be present-centered but all inclusive, we need to utilize the equanimity skill.

Here’s a subtle question. Suppose we wish to be present-centered by focusing away from thought; is equanimity still of any relevance?

The answer is yes because equanimity aids concentration. This is a general principle. Say A is your focus and B is everything else. If you want to focus on A, it’s helpful if you can let B come and go in the background without having to do anything about B. But that requires equanimity with B. Your concentration and clarity are going to A but your equanimity surrounds B allowing B to “do its thing” in the background while you focus on and vividly know A.

Summing It Up

It would seem that, regardless of how we choose to define it, present-centeredness requires three related but conceptually distinct attention skills.

Concentration, clarity and equanimity.

Conversely, any systematic exercise that develops all of these skills will allow us to be present-centered.

Perhaps these skills are in fact the defining characteristic of mindfulness and present-centeredness is just a consequence of applying these skills in certain ways (as illustrated by the three examples given above). Before considering that possibility, we need to look carefully at what we mean by “non-judgmental attention.”

Non-Judgmental

Consider the following situation.

Non-Judgment 1: No “Second Arrow”

You are bombarded by the outer senses, sight, sound, touch, but these cause no inner reaction—no judging thoughts, no pleasant or unpleasant reactive emotions. For example, even when physical pain arises, it triggers no negative tapes, no disquieting images, no emotional sensations of tear, fear, or irritation.

In the traditional metaphor, the physical pain is the “first arrow”. The first arrow is shot by external circumstances but you have, by internal volition, decided not to shoot yourself with a second arrow of reactive thoughts and emotions. The assumption here is that we may not always be able to prevent first arrows (undesirable situations) but one can learn how not to amplify it by shooting oneself with a second one.

This example is one candidate for what it might mean to be non-judgmental, but it immediately raises several questions.

1. Is it even possible to get to such a state?

2. If we claim that non-judgment is good, then judgment is bad. So aren’t we judging judging (and hence contradicting ourselves)?

3. Is it even desirable to get to such a state? Let’s explore each of these questions.

As anyone who has looked within knows, judgments and reactions arise constantly and naturally. How could one ever get to the state of “No Second Arrow”? One possibility is to keep focusing away from judgments and reactions until the habit of being judgmental weakens and eventually dies off on its own. In order for that to happen, you would have to be willing to let the judging arise and pass in the background while you focused away on something else.

In other words, you would need a sort of “second order” non-judging—you don’t judge the fact that you’re judging. Clearly this strategy for non-judgment requires concentration power (which allows you to focus away) and equanimity (i.e., “second order non-judgment”).

Another possibility would be to turn toward the judgment itself. You could break the judgment into its components (mental image, mental talk, and emotional body sensation) and untangle them. You could then observe each component in great detail and open so fully to it that it eventually dissolves into a flow of energy.

Clearly, the turn toward approach would require a lot of clarity and equanimity.

These considerations address issues one (how do we get there?) and two (judging the judging). What about question three? Judgments have a role in nature. Should we even want to be free from judgment? The answer to this question depends critically on what we mean by “free from judgment.” Free could mean:

• Never experience judgment regardless of circumstance; or

• Have the ability to be without judgment when that’s appropriate; or

• Have the ability to not identify with judgments.

The first outcome is dysfunctional. The second and third are empowering.

This clears up issue three. What’s being sought is the ability to be non-judgmental. We’re not being asked to enter an eternal suspension of critical thought.

The “Non-Judgment 1” example above shows us that the attentional skills needed to be non-judgmental are exactly the attentional skills needed to be present-centered. This lends some credence to the notion that these skills may represent the basic dimensions of mindful awareness.

One last task remains—we need to look more deeply into the relationship between “non-judgment” and “equanimity.”

So far we’ve been assuming that “judgment” is a specific type of sensory event—certain kinds of reactive mental images, mental talk, and emotional body sensations. A case could be made that the specific mental images, mental talk, and emotional body sensations that constitute the sensory experience of judgment are in fact merely the tip of a deeper, more general phenomenon.

That deeper phenomenon is a kind of pervasive subtle self-interference within our sensory systems. It’s a kind of viscosity or stickiness within the nervous system itself. A very loose analogy might be made with electrical impedance. Think of sensory experience as being like a flowing electrical current. When the current wants to arise, the system briefly impedes that by pushing down (inductive reactance). When the current wants to die away, the system momentarily impedes that by holding on a bit (capacitative reactance). Moreover, as the current is flowing, there is a kind of coagulating around it (ohmic reactance).

(A critical analysis of this metaphor will reveal fundamental flaws but hopefully it can serve to convey the general idea.)

A case could be made that this microscopic push and pull within the flow of sensory experience represents a deep and pervasive reactivity—a sort of “pre-mental judging.”

When we’re practicing “second order non-judgmentalness,” what we are in fact doing is allowing judgmental thoughts and emotions to come and go without pushing down as they arise, without holding on as they pass, and without tightening up as they continue.

Given these considerations I would claim that equanimity is a deeper and more general concept than “non- judgment.” (Once again, assuming that by non-judgmental we mean the absence of evaluative thoughts and emotions.)

Alternatively one might simply choose to broaden the definition of “non-judgment” to be synonymous with “equanimity.” In that case, we have:

• Surface equanimity – The absence of the “second arrow.”

• Deep equanimity – i.e., non self-interference within the nervous system itself.

To continues our (loose!) analogy with electric current, equanimity = admittance (the reciprocal of impedance).

Here’s a description of a way to cultivate both surface equanimity and deep equanimity with whatever comes up.

Non-Judgment 2: Equanimity

Let visual, auditory, or somatic experience come and go. Let things activate or become restful as they wish. Let things coagulate or flow as they wish.

As soon as something wants to arise, let it. As long as something wants to last, let it. As soon as something wants to pass, let it.

You may create equanimity in your body by intentionally relaxing your body or create equanimity in your mind by letting go of judging thoughts.

Above all, be sure to notice spontaneous equanimity should it occur. If you spontaneously fall into equanimity, notice that discomfort now causes you less suffering and that pleasure now gives you more fulfillment.

Analysis and Refinement

Introduction to the CCE Paradigm

It would seem that three skills

• Concentration Power

• Sensory Clarity

• Equanimity

are necessary and sufficient for present-centered, non-judgmental attention.

Perhaps this core skill set could serve as a more fine-grained definition of mindful awareness. The acronym “CCE” might be a convenient handle for this paradigm of mindful awareness.

First, let’s flesh out these skills a bit. Then we will be in a position to evaluate how well they fulfill our desiderata for a good definition of mindful awareness, i.e., to what extent is the “CCE Paradigm” for mindful awareness:

• Intuitive to the average person.

• Quantifiable in a rigorous sense.

• Mechanistically explanatory.

• Historically heuristic.

Concentration

You can think of concentration power as the ability to attend to what you deem relevant. Let’s look at how different circumstances involve different choices regarding what’s relevant.

Say you would like to maintain a focused state as you drive your car through traffic. What’s relevant to this situation?

• Visual: The sights of the road (and, occasionally, your dashboard).

• Auditory: The sounds of the road.

• Somatic: The physical sensations of being linked to the car—hands on the wheel, buns in the seat, etc. (Strictly speaking, you might need occasional thoughts to aid the driving process.)

So if you were continuously attending to just the sights, sounds, and physical sensations of driving with no irrelevant thoughts or emotions, you would experience “car-driving samādhi.” You would find that this experience has two characteristics:

1. It’s subjectively rewarding (i.e., fun).

2. It’s objectively effective (i.e., less accident prone).

We will find that this is in general true. When you are in a state of high concentration, you both feel better and perform better.

Sometimes people think that to concentrate means to focus on something exterior (as in our driving example). But you can enter a highly-concentrated state while focusing on thoughts and emotions.

For example, say you wish to deconstruct a negative urge. What sensory categories would be deemed relevant to this endeavor?

• Visual: Mental images

• Auditory: Mental talk

• Somatic: Emotional body sensations

When the negative urge is present, you could maintain continuous focus on it by attending to how it comes up in terms of those elements. Applying sensory clarity and equanimity would allow you to be less caught up in them. Taken to the limit, this process could literally evaporate the urge.

On the other hand, suppose you wanted to get insight into how self arises. You could concentrate on those same sensory elements. In concert with clarity and equanimity, this could lead to insight into the nature of self.

What if you wanted to have a really deep and fulfilling experience of listening to music? What would you deem relevant? Lots of possibilities here.

• You could concentrate on the sound only and merge with the music.

• You could concentrate on the pleasant emotional sensations the music creates in your body.

• You could concentrate on the relaxed state the music creates within you.

• You could concentrate on the energy patterns the music creates in your body.

Any one of these will greatly increase your appreciation of the music provided that you intently concentrate on it.

People tend to have certain preconceptions around the notion of concentration.

• Spatial assumption: To concentrate means to focus on something spatially small (say, the breath at the tip of your nose).

• Temporal assumption: To concentrate means to hold one experience for a long time without interruption (maintain unbroken concentration on a mantra for, say, 20 minutes).

• Suppression assumption: To concentration on a certain thing means to push everything else down/away.

• Effort assumption: To concentrate requires constant effort.

None of these assumptions are implied by the way I have defined concentration power.

• Spatial extent of concentration may be wide as well as narrow. For example, attempting to focus on your whole body at once builds/requires an expansive flavor of concentration.

• Momentarily high focus on whatever calls your attention can also build a taste of concentration. Indeed, according to Mahasi Sayadaw, such momentary penetrative concentration (khaṇikasamādhi) is one of the defining characteristics of Noting.

• To concentrate on a certain thing (selective attention) is not the same as trying to get rid of everything else (push down, push away). You can give the spotlight to a specific dancer without having to get the other dancers off stage. Indeed, allowing distractions to come and go without push and pull is one facet of equanimity.

• It is true that learning how to concentrate may require a certain amount of effort but, once you’ve done enough practice, it becomes effortless and automatic. Remember the goal is to elevate your base level of concentration—i.e., how concentrated you are in ordinary life when you’re not particularly trying to be concentrated.

Clarity

There are three sides to sensory clarity:

1. Discrimination

2. Detection

3. Penetration

The first two are relatively straightforward. Appreciating the third may require some hands-on experience.

Discrimination (or Resolution)

To appreciate what I mean by discrimination, you can do an experiment. Say you know that a certain situation may end up being an emotional challenge (but you’re not in that situation yet, so you’re still okay). As you move into that situation, emotion may begin to arise.

Discriminate: What part of the emotion is in your mind? What part of the emotion is in your body?

Further discriminate: What part of the mental emotion involves images? What part of the mental emotion involves internal talk? What are the types of emotional sensations in your body? Where are they located?

At some point, the emotional experience may become intense. Try to keep track of it in terms of how much of what, when, and where. Hopefully you won’t become overwhelmed but if you do, ask yourself the following question:

At the moment of overwhelm, was I still able to distinguish

what part of my emotion was visual thought,

what part was auditory thought,

and what part was body sensation?

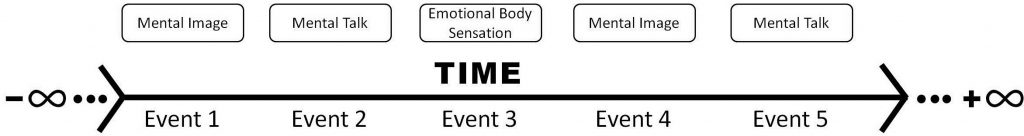

In most cases, the answer will be no. In other words, at the moment of transition between “I can handle this” to “I can’t handle this,” there will usually be a sudden and dramatic disappearance of sensory discrimination. The mental image, mental talk, and emotional body sensation are still there but suddenly you can no longer separate out what is what.

Using → to mean “implies,” we can represent this as

Overwhelm → Loss of sensory discrimination

This is an empirical truth. By that, I mean that it can be confirmed by repeatedly doing experiments like the one described above.

Amazingly, the reverse of the above statement is also true.

No loss of sensory discrimination → No overwhelm

But sensory discrimination can be strengthened by systematic practice. Symbolically:

Systematic and sustained practice → Stronger sensory discrimination

Taken together, this leads to an extraordinary conclusion:

Mindfulness Practice → More sensory discrimination → Less overwhelm in daily life

Detection (or Sensitivity)

The detection dimension of clarity involves:

• An intensity-related aspect: the ability to detect subtle faint signals.

• A time-related aspect: the ability to spot short, fleeting events. Let’s briefly examine each.

Faint Signals

In the previous section, I described the process of untangling the strands of mind-body experience. But you cannot untangle sensory strands unless you can consciously detect them. The relevant mental images and emotional body sensations are often below the threshold of awareness. That’s one reason people act in regrettable ways without really knowing why.

As your sensory clarity increases, you begin to detect (previously) subliminal mental associations and (previously) unconscious body sensations. Those sensory strands now become trackable. What is trackable is tractable.

Both detection and discrimination are key skills needed to eliminate emotional hijacking.

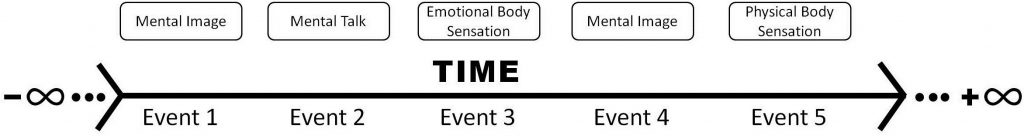

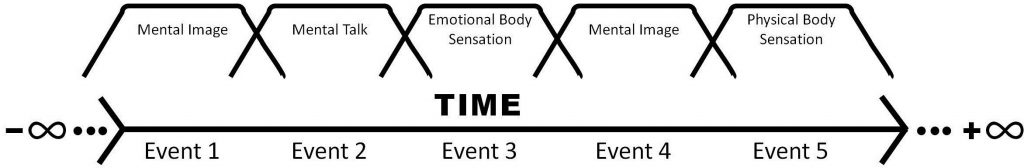

Let’s go back to our initial example of untangling mental image, mental talk, and emotional body sensation. We could visually represent that untangling like this:

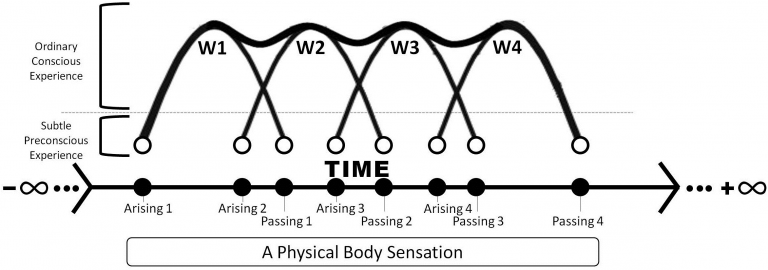

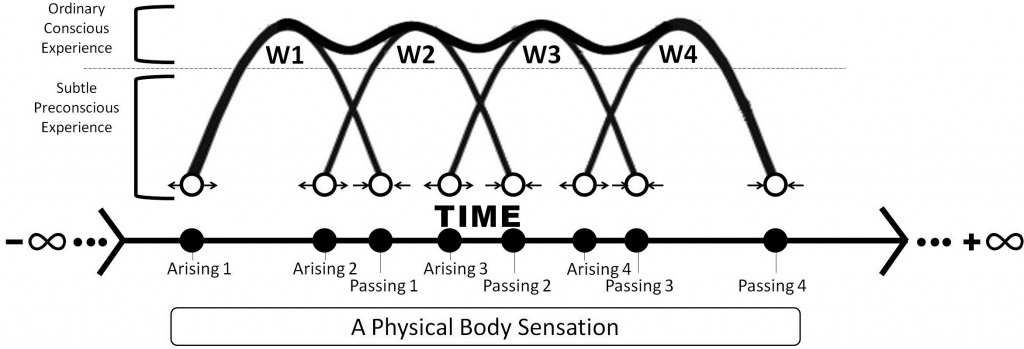

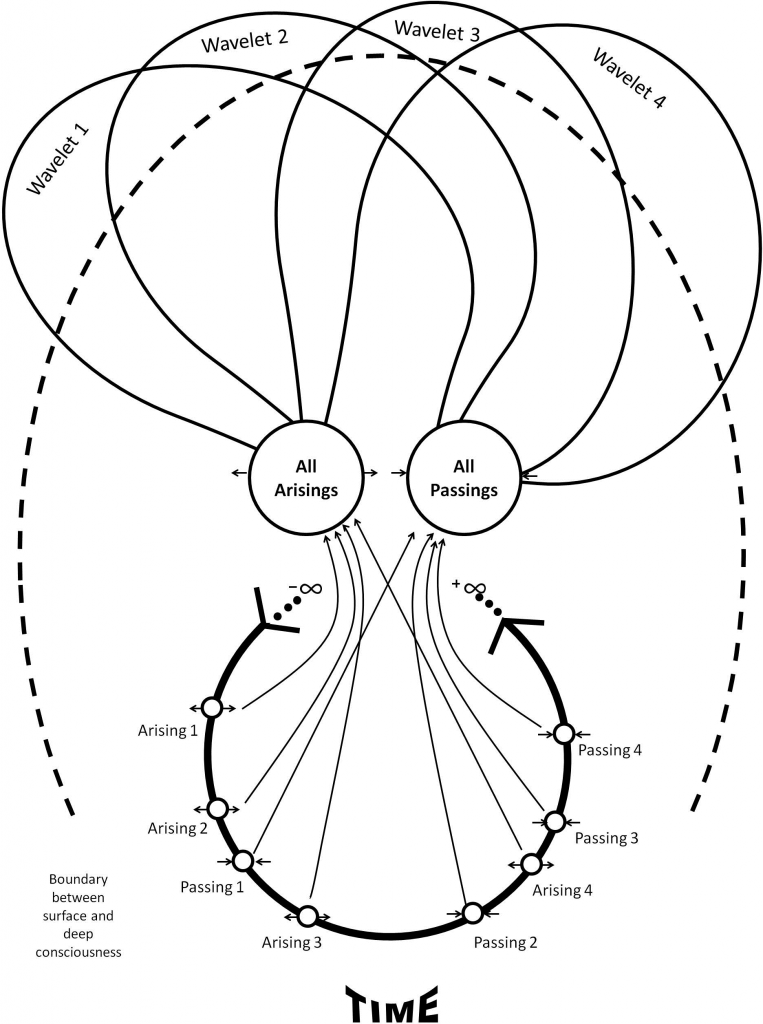

Now let’s add the ability to detect subtle fluctuations and the ability to detect moments arising and passing.

Notice that we now have a much clearer picture. Not only are the individual events distinct but we are detecting:

• The moment when an event arises.

• The moment when an event passes.

This gives us insight into the wave nature of these experiences.

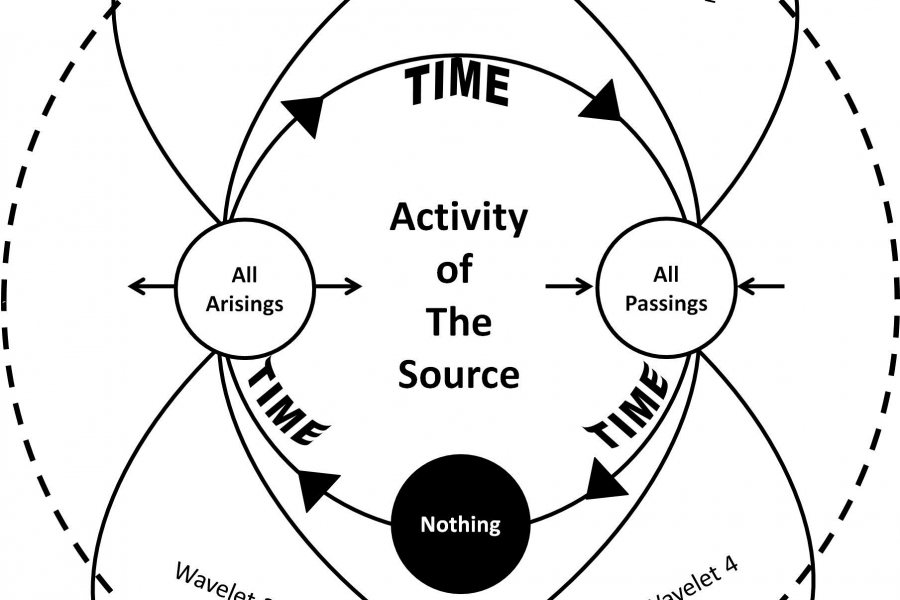

Moreover, we are starting to see that these events are not solid. Their surface contour is ripply and vibratory. Apparently the waves themselves are made up of wavelets!

Penetration

Burmese Sayadaws (mindfulness masters) sometimes describe awareness as being like a dart or arrow. The object of awareness (a sound, a mental image, a body sensation, and such.) is like a target. During mindfulness practice, you hurl your attention into each sensory event giving the awareness enough momentum to briefly penetrate that target, i.e., know it through and through down to the tiniest level of detail.

According to these Sayadaws, the original meaning of the Pali word satipaṭṭhāna is “to penetrate with awareness”:

sati – awareness, attention

paṭṭhāna – to thrust against (from sthāna – stand [in the transitive sense] and pra – forth, out)

When I first heard mindfulness characterized this way, I didn’t get it. I was even a bit put off by what seems to be an almost violent metaphor. Eventually, I came to experientially understand what the Sayadaws were trying to convey. Over the years, I’ve come up with a bunch of other metaphors, viz:

The Thirsty Sponge. Awareness is like water. The sensory event is like a sponge. The water soaks into the sponge, filling every fold and crevice.

The Busy Bee. Awareness is like a bee. The sensory event is like a flower. The bee buzzes around within the flower leaving no petal unknown.

The Lake and the Torch. Sensory events are like a lake. Awareness is like a flashlight.

The surface of the water represents the part of sensory event that’s conscious. The water just below the surface represents the parts of the sensory event that are peripherally conscious. The mid-depth water represents sub-conscious neural processing. The water at the bottom of the lake represents unconscious neural processing.

Directing the flashlight towards a spot on the surface of the lake effects all four levels simultaneously.

What’s on the surface becomes much clearer than it ordinarily is. What’s just below now becomes as clear as the surface had been. What was subconscious now becomes peripherally conscious. What was utterly unconscious now becomes somewhat conscious.

Thus the subconscious/unconscious levels of processing get to know themselves a bit better. You (the observer directing the flashlight) still cannot directly see all levels but some photons of clarity have trickled down, giving those levels what they need to untie their own knots.

It’s quite common for people to report that during formal practice, nothing much seems to happen. Yet they notice spontaneous and permanent improvements in perception and behavior in daily life. The penetration (or trickle down) paradigm described here is one way to explain why that happens.

English and other European languages have an interesting idiosyncratic usage around the verb “to know.” It is occasionally used as a euphemism for “have sex with.” This is sometimes referred to as “known in the Biblical sense.” It represents the influence of Old Testament Hebrew on the languages of the Christian West.

Hebrew distinguishes three “flavors” of knowing.

binah – To know in a separating/distinguishing way.

da’at – To know in an intimate/penetrative way.

chochmah – To know in an insight/wisdom way

The second word is the source of our “carnal knowledge” euphemism. What’s interesting is how this maps on to mindfulness practice.

Binah is the clear acknowledging that separates the strands of sensory experience, distinguishing:

• Visual vs auditory vs somatic

• Inner vs outer

• Activity vs restful

• Stability vs flow

Da’at is the intent focusing that knows a given sensory strand through and through, right down to the vibrating void which is its substance.

Chochmah is the insights, the a-ha epiphanies that arise as a result of knowing in the other two ways.

As we have seen, the English word mindfulness can translate several Pali terms. Among them are satipaṭṭhāna

(described above) and vipassanā. Let’s look at the word vipassanā.

Vi is a prefix that modifies a verb.

Passanā means seeing.

As a prefix, vi can mean three things: “separate,” “through,” and “in a special way.”

So vipassanā refers to a single process that involves

seeing separate, i.e., untangling (binah)

seeing through, i.e., penetrating (da’at)

seeing in a new special way, i.e., insight/wisdom (chochmah)

The three Hebrew words can also be put together to form a single acronym Chabad, the name of a prominent Hasidic organization.

Equanimity

Equanimity is a fundamental skill for self-exploration and emotional intelligence. It is a deep and subtle concept frequently misunderstood and easily confused with suppression of feeling, apathy or inexpressiveness.

Equanimity comes from the Latin word aequus, meaning balanced, and animus, meaning spirit or internal state. As an initial step in understanding this concept, let’s consider for a moment its opposite: what happens when a person loses internal balance.

In the physical world we say a person has lost balance if they fall to one side or another. In the same way a person loses internal balance if they fall into one or the other of the following contrasting reactions:

• Suppression – A (internal or external) sensory experience arises and we attempt to cope with it by stuffing it down, denying it, tightening around it, etc.

• Identification – A (internal or external) sensory experience arises and we fixate on it, hold onto it inappropriately, not letting it arise, spread, and pass with its natural rhythm.

Between suppression on one side and identification on the other lies a third possibility, the balanced state of non-self-interference…equanimity.

How to Develop Equanimity

Developing equanimity involves the following aspects:

• Intentionally creating equanimity in your body;

• Intentionally creating equanimity in your mind; and

• Noticing when you spontaneously drop into states of equanimity.

Intentionally Creating Equanimity in Your Body

This is essentially equivalent to attempting to maintain a continuous relaxed state over your whole body as sensations (pleasant, unpleasant, strong, subtle, physical, emotional) wash through.

Intentionally Creating Equanimity in Your Mind

This means attempting to let go of negative judgments about what you are experiencing or replacing them with an attitude of loving acceptance and gentle matter-of-factness.

Let me give you a tangible example of how equanimity can be created.

Let’s say that you have a strong sensation in one part of your body. As you focus attention on what is happening over your whole body, you notice that you are tensing your jaw, clenching your fists, tightening your gut, and scrunching your shoulders. Each time you become aware of tensing in some area, you intentionally relax it to whatever degree possible. A moment later you may notice that the tensing has started again in some area; once again gently relax it to whatever degree possible. If there are areas that cannot be relaxed much or at all, you try to accept the tension sensations and just observe them. As a result of maintaining this whole-body relaxed state, you may begin to notice subtle flavors of sensation spreading from the local area of intensity and coursing through your body. These are the sensations that you had been masking by tension.

Now that they have been uncovered, try to create a mental attitude of welcoming them or not judging them. Observe them with gentle matter of-factness, giving them permission to dance their dance, to flow as they wish through your body.

Noticing When You Spontaneously Drop into States of Equanimity

From time to time, as we are passing through various experiences, we simply “fall into” states of greater equanimity. If we are alert to this whenever it happens and use it as an opportunity to explore the nature of equanimity, then it will happen more frequently and last longer.

For example, let’s say that you have been working with a physical discomfort. At some point you notice that even though the discomfort level itself has not changed, it somehow seems to bother you less. Upon investigation you realize that you have spontaneously fallen into a state of gentle matter-of-factness. By being alert to this and by exploring the state, you are training your subconscious to produce the state more frequently.

The Effects of Equanimity

Equanimity belies the adage that you cannot “have your cake and eat it too.” When you apply equanimity to unpleasant sensations, they flow more readily and as a result cause less suffering.

When you apply equanimity to pleasant sensations, they also flow more readily and as a result deliver deeper fulfillment. The same skill positively affects both sides of the sensation picture.

Hence the following equation:

Psycho-spiritual Purification = (Unpleasant experience x Equanimity) + (Pleasant Experience x Equanimity)

Furthermore, when feelings are experienced with equanimity, they cease to drive and distort behavior and instead assume their proper function of motivating and directing behavior. Thus equanimity plays a critical role

in changing negative behaviors such as substance and alcohol abuse, compulsive eating, anger, violence, and so forth.

You can also have equanimity with thoughts. You can let positive and negative thoughts come and go without push or pull. You can let sense and non-sense arise and pass without preferring one over the other. This will result in a new kind of knowing—a kind of wisdom function (prajñā). Equanimity with thought allows you to work through the drivenness to think. When compulsive eaters work through the drive to eat, they don’t stop eating, they simply eat in a new and better way. When compulsive thinkers (i.e., just about everyone) work through the drive to think, they don’t stop thinking, they just begin to think in a new and better way.

Equanimity, Apathy and Suppression

Equanimity involves non-interference with the natural flow of sensory experience. Apathy implies indifference to the controllable outcome of objective events. Thus, although seemingly similar, equanimity and apathy are actually opposites. Equanimity frees up internal energy for responding to external situations.

By definition, equanimity involves a radical permission to experience your senses and as such is the opposite of suppression. As far as external expression of feeling is concerned, internal equanimity gives one the freedom to externally express or not, depending on what is appropriate to the situation.

Passion and Dispassion

Passion is an ambiguous word with at least four meanings:

1. Deep poignancy of feeling;

2. Unhindered expression of feeling;

3. Dynamic behavior that rides on deep feeling; and

4. Suffering and behavior distortion caused by feeling that is experienced without sufficient equanimity.

Due to this ambiguity, one could validly claim that people become more passionate as they learn to be dispassionate—i.e., 1, 2, and 3 increase as 4 decreases.

Physical Analogies for Equanimity

Developing equanimity is analogous to:

• Reducing friction in a mechanical system (Equanimity =1/F);

• Reducing viscosity in a hydrodynamic system (Equanimity =1/μ);

• Reducing resistance in a DC circuit (Equanimity =1/R);

• Reducing impedance in an AC circuit (Equanimity =1/Z);

• Reducing stiffness in a spring (Equanimity =1/k); and

• A solution being thixotropic as opposed to rheopectic. (Thixotropic substances, such as paint, thin out when they get stirred. By way of contrast, rheopectic substances, such as corn starch, thicken up when they get stirred.)

Extending these metaphors, perfect equanimity would be analogous to “superconductivity” within all your sensory circuits.

Another Synonym for Equanimity

Love.

Equanimity in Christianity

Early and medieval Christianity placed a great value on equanimity. Indeed it was considered one of the primary Christian virtues. This is because Christianity viewed itself as a path of radical spiritual cleansing (katharsis), with equanimity as the main tool for achieving this goal.

The church fathers, who wrote primarily in Greek, had three words for equanimity:

Nepsis: “Sober observation”

Ataraxia: “Freedom from upset”

Apathia: “Dispassion”(Note: In this usage, apathia does not equal apathy!)

In Christianity, the theory of purification through equanimity constituted a major branch of spiritual study known technically as “Ascetical Theology.”

Equanimity in Judaism and Islam